One of the coolest things about technological progress is that it feeds on itself. New technologies generally make new processes feasible (or possible), and this inevitably leads to new toys tools that we engineers can use to make even cooler stuff.

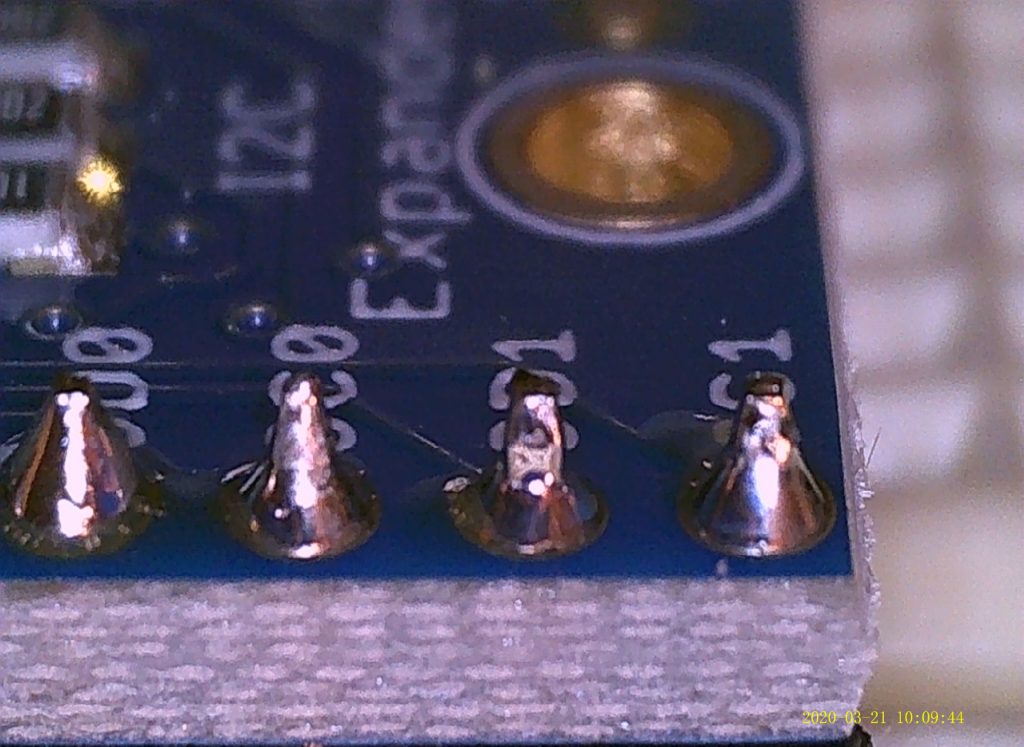

Recently, inexpensive consumer-grade digital “microscopes” have gotten pretty good, at least in terms of imaging. For around $65US, you can get a CCD “microscope” that can produce clear images at something like 60x magnification and can resolve objects down to something like 10-20 microns. While this isn’t anywhere near the performance of a professional microscope, it’s a very useful benchtop tool — with a few caveats.

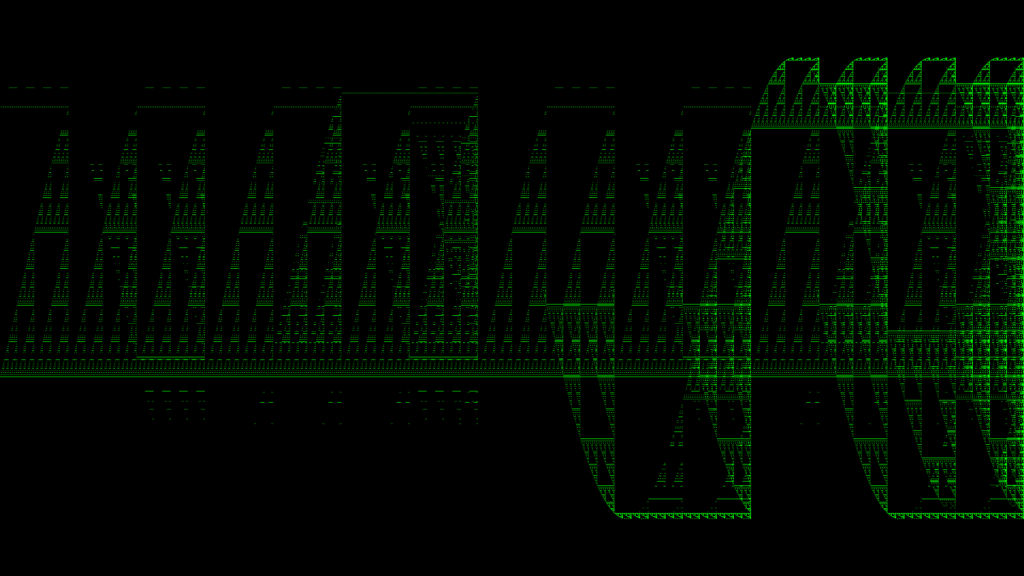

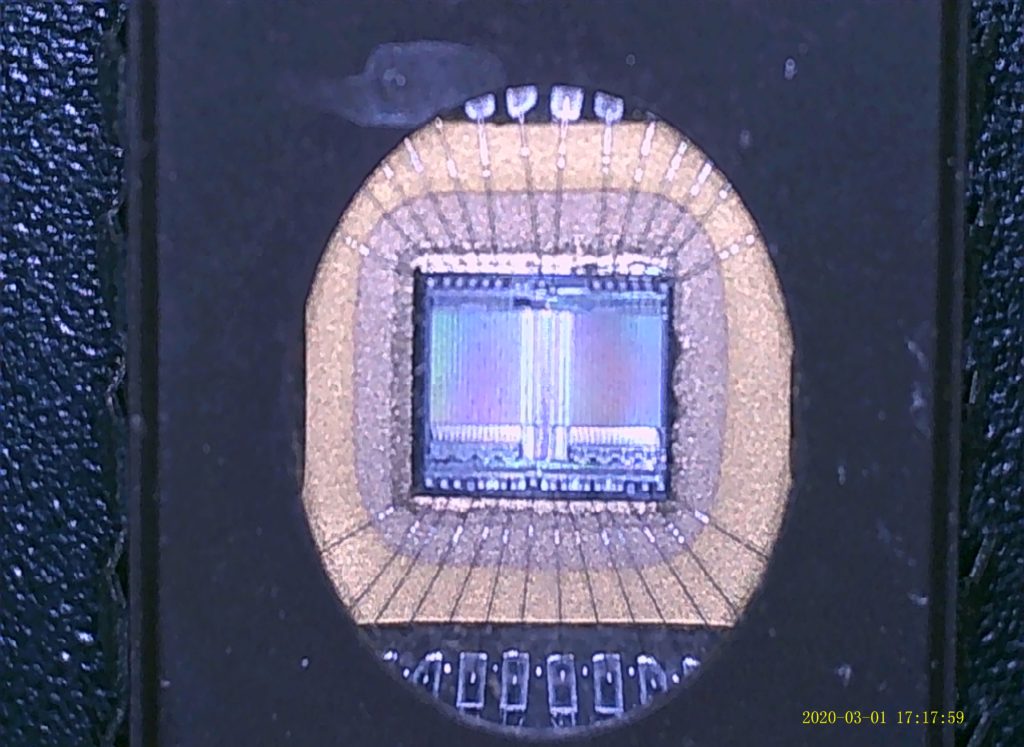

(This is the minimum zoom achievable with the stock stage.)

The biggest problems are related to the mounting. The camera may well have a 10MP sensor (hard to say; the images come out at 10MP but are .jpgs and may be upscaled) — but the mounting stand is cheap and tends to shake and flex when used. Maximum zoom is limited by the optics, which can only focus down to a minimum distance of a few centimeters from the object. Minimum zoom is limited only by the maximum height to which the mounting can move the camera; the optics themselves are capable of focusing on objects at infinity. Vertical movement is accomplished by a rack-and-pinion system which, being mostly plastic, binds up, preventing smooth motion, and has far too much backlash / hysteresis.

Many of these problems can be corrected by mounting the camera securely to a better gantry, such as a 3D printer or CNC mill. For board-inspection work such as the inspection of solder joints, the existing stage works reasonably well. Still, an additional $10 or $20 cost would have been a small price to pay for a more solid mounting and maybe metal or even nylon gears.

Once you work around the mounting limitations, though, the images aren’t bad…

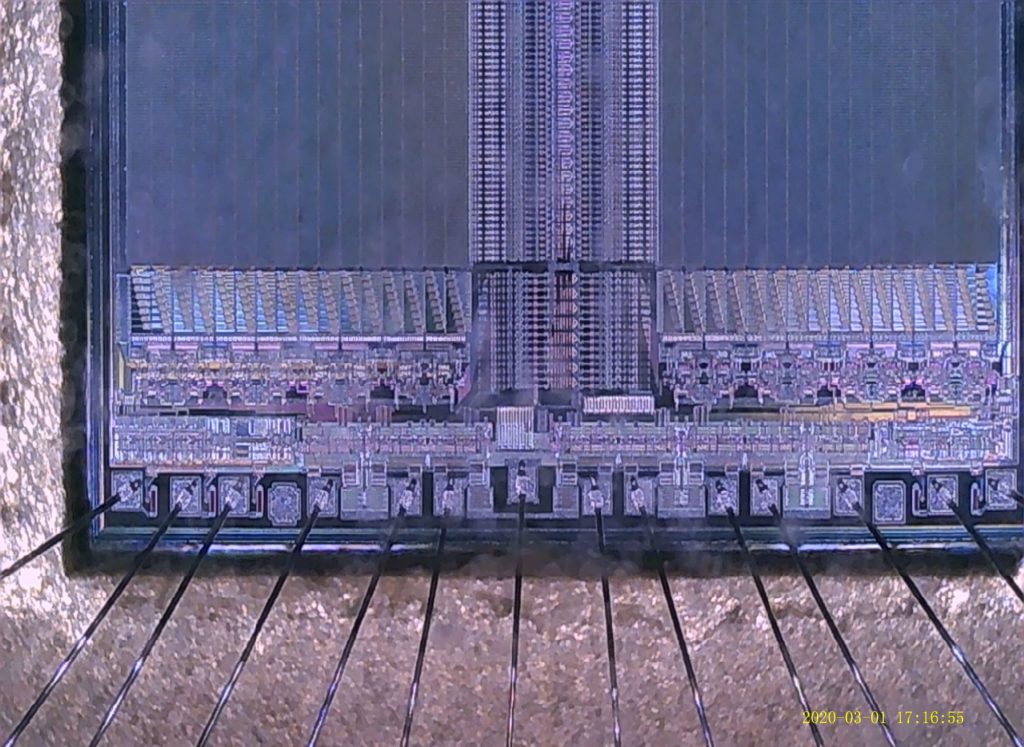

For scale, these pins are spaced 2.54mm (0.1″) apart.

This is a DIP28 600-mil package, so it’s roughly 15-16mm (0.6″) across.

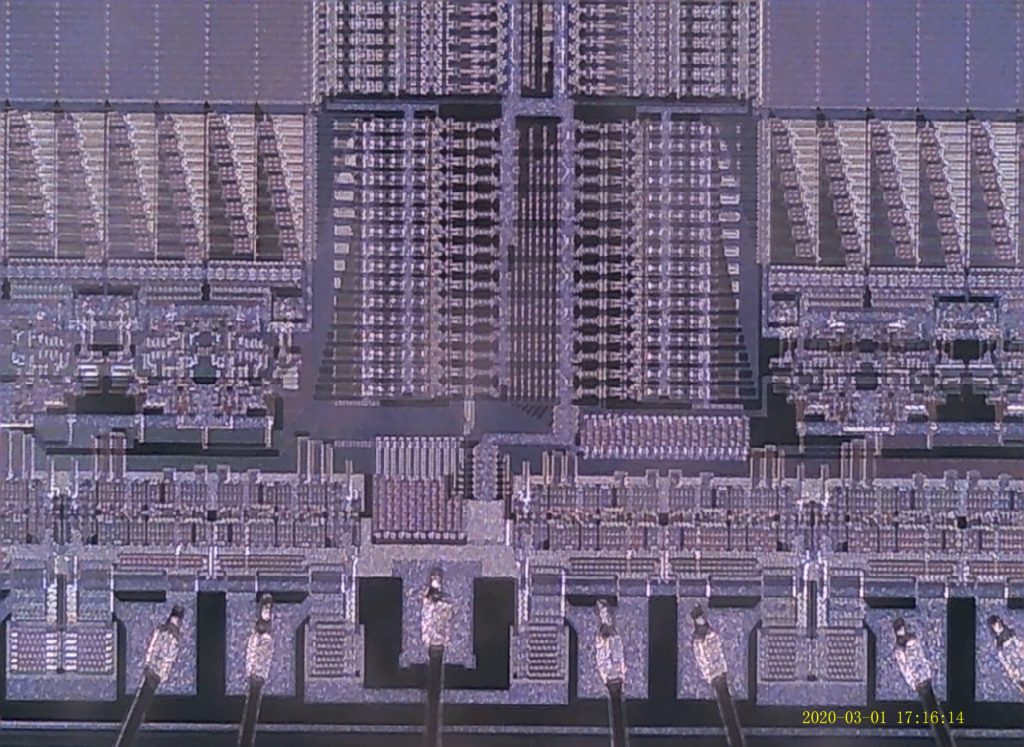

You can almost see individual transistors, if still indistinctly.

(Click for original image for this and the others.)

It’s not very helpful for soldering — at least, not for 0.1″ pins — that goes much faster just looking at them the old-fashioned way. As it is, though, it’s certainly worth $65 or so for an excellent digital magnifying glass. It’s great for board inspections; you can clearly see all kinds of details that you’d miss even with a nice traditional magnifying glass.

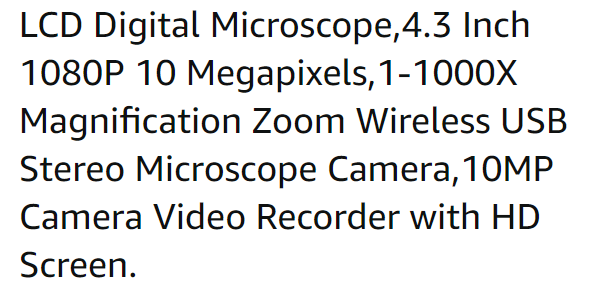

Just don’t believe all of the terms that they put in the product description. Here’s the truth:

- LCD: Yes, it has a decent LCD display.

- Digital: Check.

- Microscope: Yes, if maybe not quite the 1000x zoom it claims. (See below.)

- 4.3 inch: The display measures 110mm (~4.33″) diagonally (and uses it all). Check.

- 1080p: No. It can do video over USB, but its maximum resolution is a (clear) 720p.

- 10 Megapixels: It can produce 3840 x 2800, 24-bit .jpg files on the 10MP setting.

So either it does take 10MP images, or at least it upsamples them to this. - 1-1000x magnification zoom: I was able to enlarge a pin measuring 580 microns

across to roughly one foot across on my 45″ monitor.

If you have a giant monitor, maybe 1000x?? - Wireless: No. It’s “wireless” in that it has a Li-Ion battery, and

can capture images and videos by itself. It needs a wired USB link for use with a PC.

It doesn’t seem to have any kind of radio link like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, etc. - USB: It can charge via Micro USB as well as act as a PC camera over USB.

It can likely transfer pictures via USB, too. (So far, I’ve just used the MicroSD card.) - Stereo: This one boggles the mind. I think the video record feature also records audio.

…Maybe they’re referring to this? It is NOT a stereo microscope. Not at this price. - Microscope: Yes; up to maybe 500x or so on a reasonably large monitor.

- Camera: Yes.

- 10MP: Maybe?

- Camera video recorder: It does record video, although not at 10MP, of course.

- with HD screen: Probably not. It’s probably 640×480 or something like that. It’s adequate.

Bottom line: I’d buy it again. It’s useful enough, even if the claims are a little exaggerated.