Back when I was in first or second grade (so, sometime in the 1979-1981 timeframe), the sixth graders put on a musical skit about life in The Future. I don’t remember much about it, except everybody was dressed in shiny “futuristic” clothes, mirrored sunglasses, and had flying cars. They sung about what life was supposedly like — I don’t remember the details, except they were very excited to live in The Future, and kept enthusiastically singing, “It’s Twenty-Twenty-Four!!”

Well, here we are. It’s actually 2024. It’s officially The Future, at least as 1980 or so saw it. What would my 1980 counterpart think about modern life, if he got to spend a day in the real 2024?

Well, first, I’d have to coax him away from staring at the 4k monitor I picked up last Fall. “TV” screens are much larger and brighter — but far lighter — than anything 1980 had imagined. Even the expensive projection TVs from back then don’t come close to a $300 OLED monitor.

And then there’s the content. YouTube is better TV than 99% of TV, easily. I’m going to have a better idea of what I want to watch than some TV network executive. Whatever you want to learn — from playing the ukulele to deep learning — has tutorials ready to be watched, 24/7.

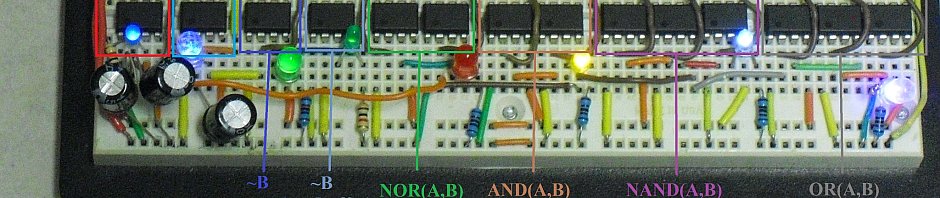

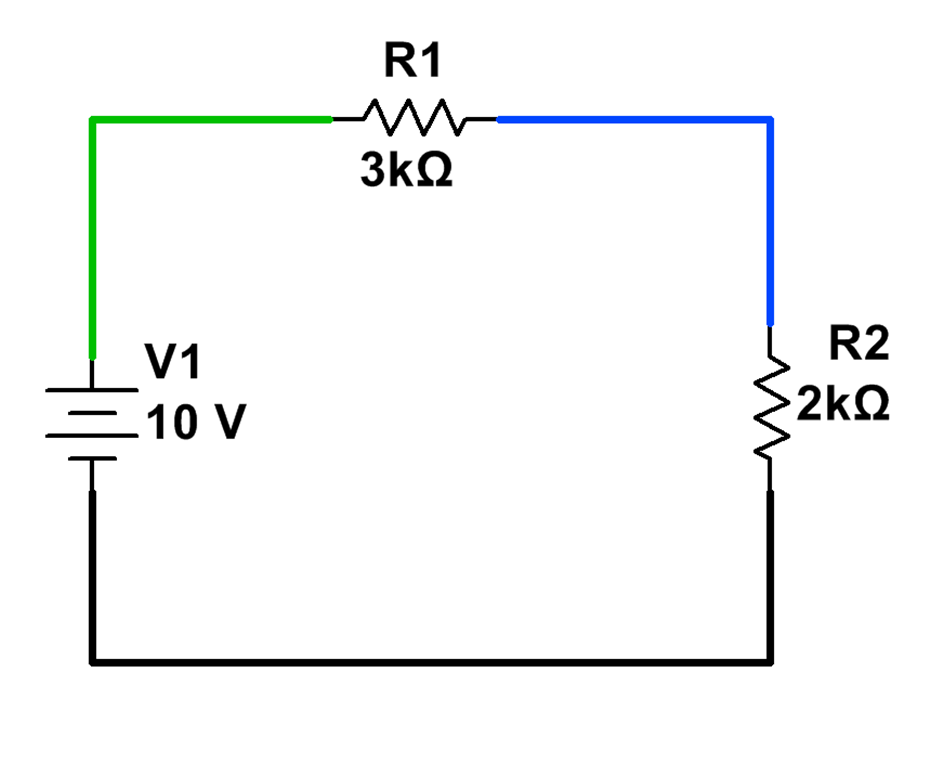

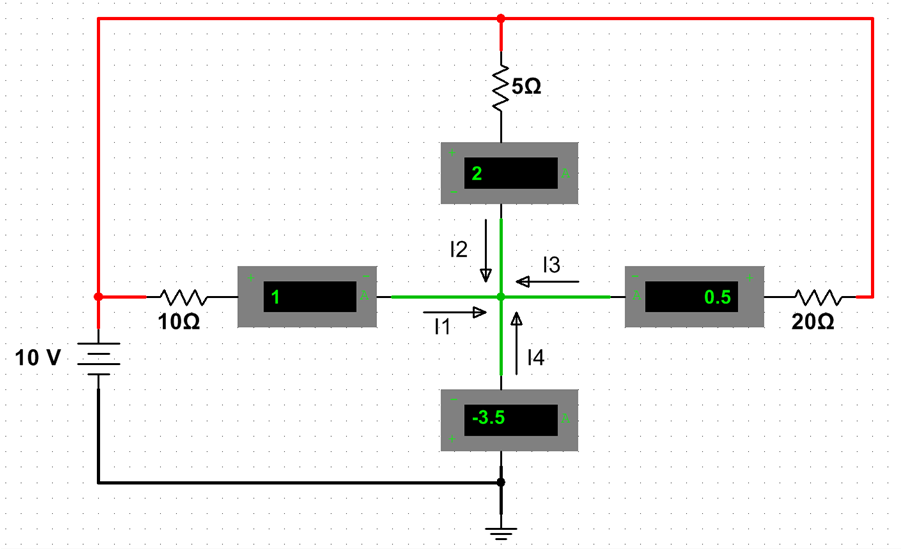

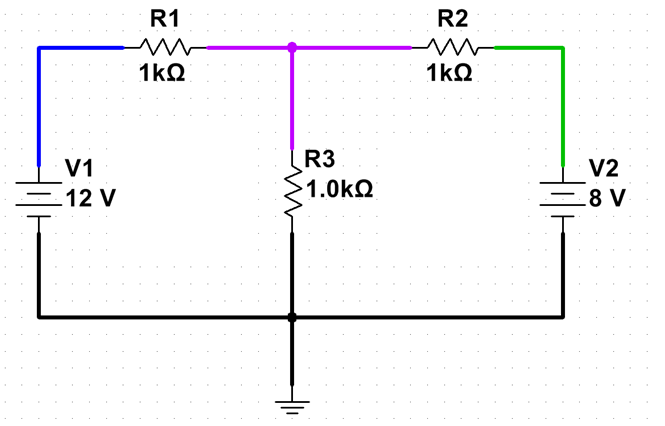

To distract my younger self before he finds out about Reddit, I show him a 3D printer and a laser cutter/engraver. Some similar technology did exist back then, but only in industry — the catalyst for the 3D printer hobby explosion was the expiration of some key patents around 2010. “So you have toys that can make other toys,” he observes, as a Benchy starts to print. It’s a great time for hobby electronics in general, I point out, as I show him all of the local aircraft that I can track with my home ADS-B setup.

So do we have flying cars? Well, not really. Honestly, even 1980 would understand that it’s dangerous enough to trust people with driving in 2D, and without the careful training that pilots have to pass in order to be licensed, flying cars would not end well. We do know how to make flying cars (some of them have been around for decades), but the old wisdom that cars make poor airplanes and airplanes make poor cars is still generally true.

We do have some amazing tech in “normal” cars, though. I pull out my Android smartphone (a 2022 model, but still so far beyond any tech 1980 had that it would look like magic) and reserving an Uber. A few minutes later, a sleek-looking white car pulls up, making very little noise. 1980-me comments that the engine is very quiet; I tell him that’s because it doesn’t have one. The driver obliges us by giving us a quick demonstration of its acceleration — comparable to the huge, powerful muscle cars of the 1960s, only almost silent. And we’re probably close to having self-driving cars (full autopilot) commonly available.

“It knows where it is,” 1980-me comments, looking at the moving map display. I explain about GPS and satellite navigation, and how “being lost” is generally very easy to fix, now. He asks if privacy is a concern, and is happy to hear that GPS is receive-only — the satellites don’t know and don’t care who’s using the signals. I decide not to mention all the many ways in which we are tracked, if maybe not geographically.

We head back home. “So, how fast are modern computers compared to what we have in 1980?” I explain about multi-core CPUs, cache memory, gigahertz clock speeds, pipelining, and such. He mentions that he wrote a program in BASIC to calculate prime numbers, and remembered that it took four minutes to find the prime numbers up to 600.

I code the same problem up in FreeBasic on my Windows PC. It takes ten milliseconds. After explaining what a millisecond is (and how it’s actually considered fairly long, in computing terms), we calculate that my modern PC is more than 24,000 times faster. To be fair, this is pitting compiled 64-bit code on the Core i9 against interpreted BASIC on the 1982-era Sinclair — but on the other hand, we’re not making use of the other fifteen logical processors, or the GPU. We race a Sinclair emulator (“your computer can just pretend to be another one?”) to compute the primes up through 10,000. The i9 does even better — some 80,000x faster.

I do the calculation in my head, but don’t mention the more than eight million times difference in memory size between the Sinclair and the i9’s 128GB. (It would be 64 million times, without the Sinclair’s wonky, unreliable add-on memory pack!) First graders don’t yet really have a good intuition for just how big a million is, anyway.

“So, what are video games like?” I put the Quest 2 headset on him and boot up Skyrim VR. He enjoys it — at least right up until he gets too close to the first dragon and gets munched. He loves Minecraft, of course — “It’s like having an infinite Lego set and your own world to build in!”

Then I show him Flight Simulator 2020 and the PMDG 737. He hasn’t found the power switch yet (it’s not super obvious), but he hasn’t stopped grinning, either. And he has yet to meet GPT4 and friends. Or to listen to my mp3 collection.

I love living in the future.