I’m not a fan of spicy foods. Heinz 57 is, for me, what hot sauce is for most normal people. I never understood the appeal of black pepper, since it tastes like hot coals on my tongue. Similarly, I usually find garlic to be overpowering and painful rather than flavorful to taste, and only really used it in garlic bread as an excuse to consume butter.

Then, shopping in Wegmans one day a couple of years ago, I discovered black garlic. It’s botanically still garlic — but completely different. When garlic cloves are gently heated over the course of several weeks, they undergo a Maillard reaction that breaks down the sharp garlicky enzymes into smoother, subtler sweet and umami flavors. Just like time can turn grape juice into wine, a couple of months of gentle heat can turn cloves of garlic into something magical.

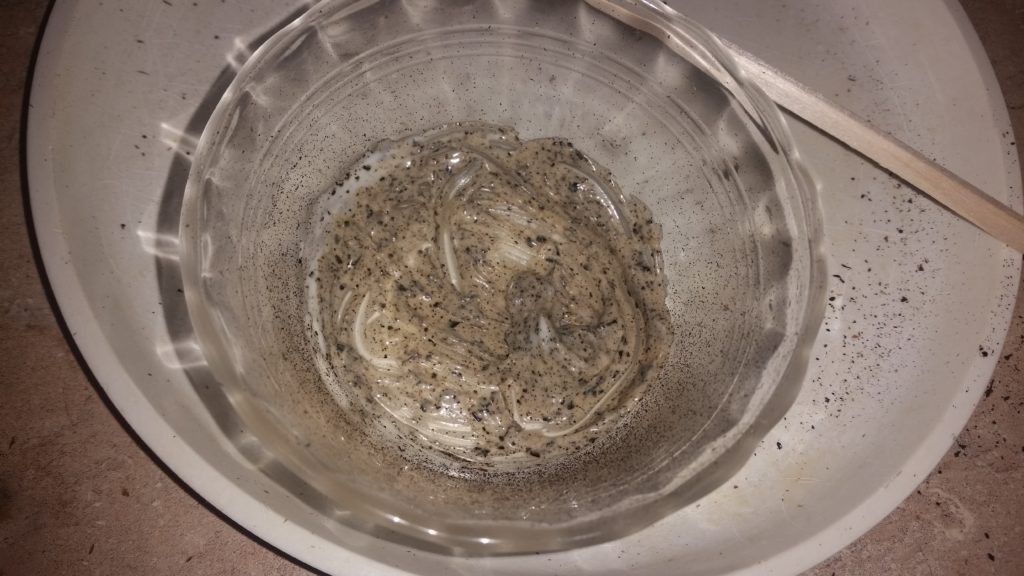

(Two months ago, this was a bulb of fresh, white garlic.)

The recipe is a lot simpler than you might think. Wrap bulbs of fresh garlic (the same kind you’d use to sort out a vampire problem) tightly in plastic wrap and then aluminum foil, place them in a smart pot or crock pot with Keep Warm setting, and leave them alone for six to eight weeks. (I started mine at the end of August and harvested today, November 1st.) You could probably pack the cooker full, if you wanted to do a lot of them. Yield is one bulb per bulb.)

NOTE: DO NOT USE A “COOK” SETTING — EVEN “LOW.”

You want the bulbs to stay in a warm, humid environment — around 85% humidity and 70C.

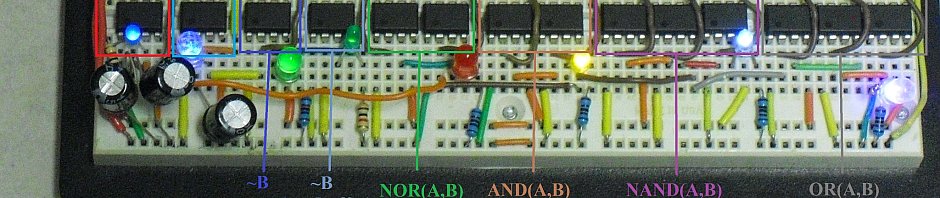

These are done — but you can’t tell without opening them (or smelling them.)

After a couple months in the cooker (pro tip: get one that doesn’t helpfully turn itself off periodically), they’re done. Shut it down, let them cool, and unwrap…

Taking one clove apart for science reveals a complete transformation inside — the cloves have been transformed from pungent, acrid fresh garlic into coal-black lumps. Separating them from the garlic skin, I got about 22g of cloves from one bulb.

I believe they should be sticky and gummy; these were hard and dry.

The black garlic I bought from Wegmans had sticky, gummy cloves — which were messier to extract but tasted great. The ones from this homemade batch were hard and dry — very easy to clean up, but slightly bitter-tasting along with the characteristic sweet umami flavor. It’s nothing a dash of sugar won’t fix, but I may try cooking the next batch for six weeks instead of two months.

Not bad, but slightly bitter. Two months may be a couple weeks too long.

To make your own:

* Wrap bulbs of fresh garlic in plastic wrap and then aluminum foil;

* Place them in a covered smart pot or crock pot (on Keep Warm) for about six weeks;

* That’s it. Enjoy!