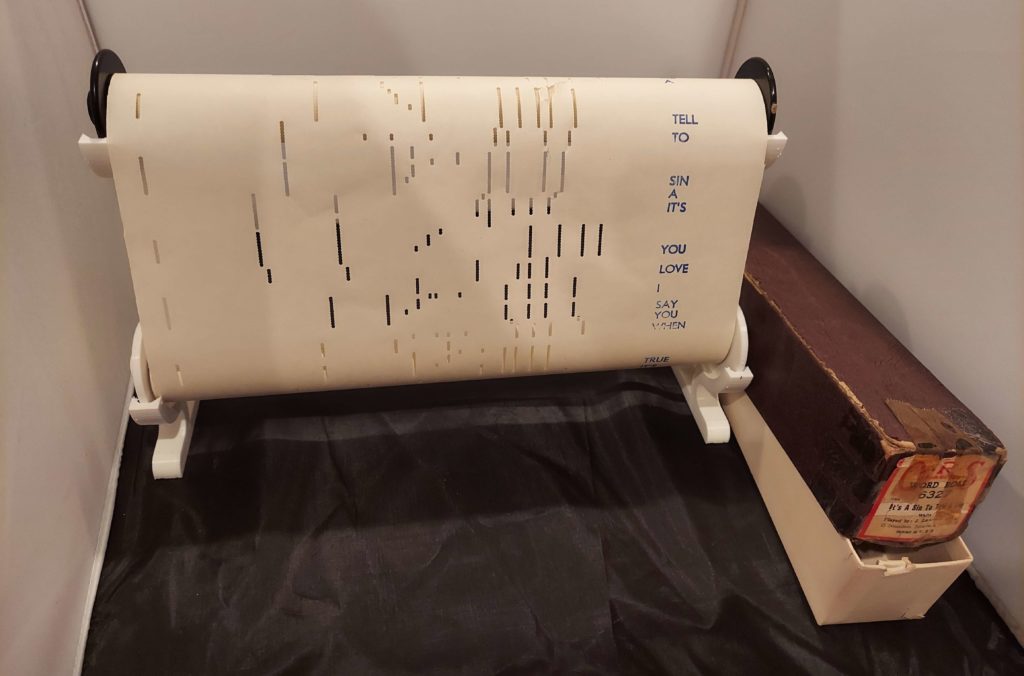

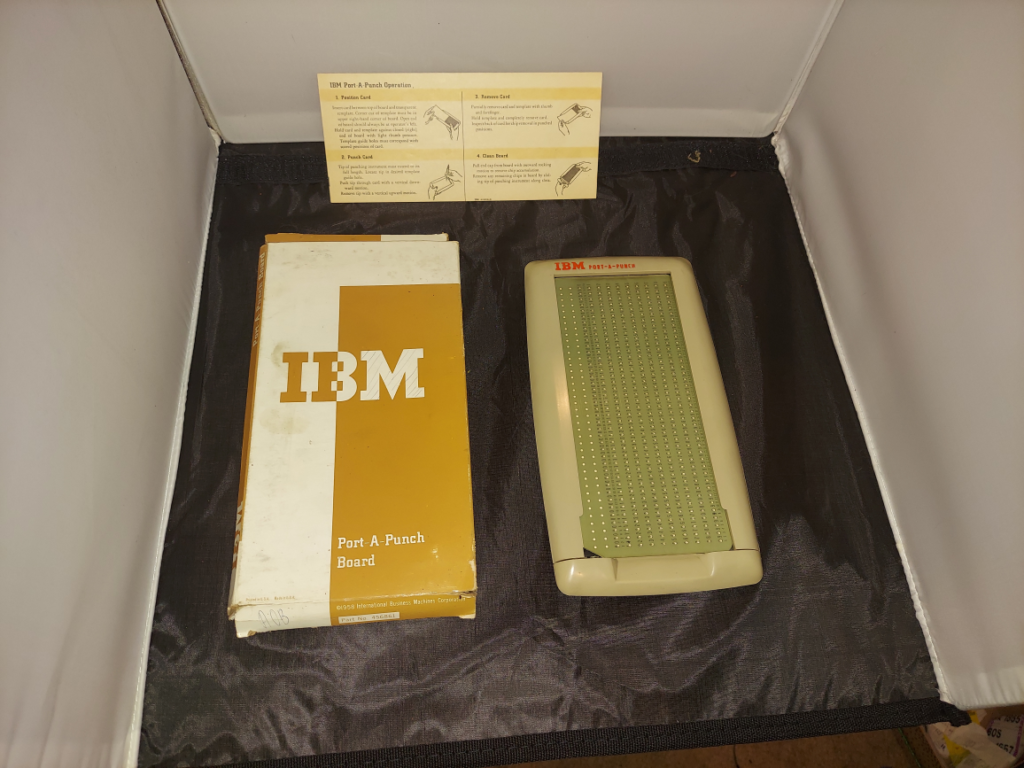

Data storage, even on electronic computers, wasn’t always done electronically or even electromagnetically. In the mid 20th century, paper card stock was used to store information by the presence or absence of punched holes in the cards. Although the storage density of such media (one bit per punch position) is orders of magnitude less than modern devices like SD cards (or even floppy disks), one benefit is that the data can be manually created. The only tool required is basically a sharp stick.

With such a tool, programmers could make their own cards without needing to sit down and use a full-size card punch. While the handheld tool probably wouldn’t be the best choice for coding up an operating system, it could allow data collection out in the field. Ask your questions and record your responses on punched cards, ready to be fed into the computer.

Automatic card and tape punches even had a “bit bucket,” where punched-out bits would go to be discarded. (This was before recycling; at least paper is biodegradable.)

…What won’t they think of next?